How Do You Handle Black Death?

by Rev. Dr. Starsky Wilson

Yesterday, I yelled at my sons.

I am no saint. It was not the first time. But it was different. This was not simply a ‘you can make better grades than this’ or ‘why can’t you keep your room clean’ moment. I went off.

They were being boys. Playing their Nintendo Switch games. Because my wife and I have restricted their access, they were excited about the 90 minutes we gave them to connect with one another and their friends through the game in competition. In the midst of the battle, their four-year-old sister had needs of her own that she called on them to meet. She had no idea that she was encroaching upon sacred, limited game time. So, one of them raised his voice at her…and daddy ain’t having that. After a brief paternal intervention, all was well.

But just a few minutes later, tension crept up within the game environment that caused one of my sons to come into the room with me frustrated at his other two brothers and wrestling with how to hold in his emotions. At this point all things had to cease. I took all the games and shut down the makeshift arcade at the dining room table.

I gave them a lecture and a tongue lashing longer than normal for this type of juvenile infraction. I talked to them about the need to care for one another’s emotions, to tend to one another as siblings, and to (using the church language) “bear one another’s burdens.” Truth be told, under other circumstances this incident did not require a lecture. They are good boys (not perfect, but good boys) who already knew and daily exercised everything I was expressing in that moment.

They did not need to be yelled at.

What was really happening was my own stuff was bubbling over from what I had just experienced as the tipping point of my capacity to manage the death, destruction, and danger that surrounded them and me. My deep frustration and anxiety about how to keep my three brilliant, beautiful and bold black boys safe from harm came out from deep within me and poured out on them.

They didn’t know that while they were playing their games in the dining room, I was watching a live feed on cable news in the living room. They did not know that I had just processed the leader of the free world and the commander-in-chief of the largest, strongest, most dangerous armed services unit on the face of the globe and in history, turn tax-payer funded weaponry on ‘the people’ gathered in front of ‘the People’s House.’ They had no idea that these citizens were targeted for exercising the freedom of speech and civic engagement that I was raising them to exemplify.

My sons had not heard the speech from the Rose Garden in which an American president elected by a minority of the American population lied about the law and his capacity to direct military troops into the cities of the United States where primarily black people live. And they surely did not understand that seeing him stand in front of God’s church holding up the holy book to which we attempt to circumscribe our family life reminded me that all sustainable forms of oppression in history have theological legitimization and use religious symbolism.

My sons did not need to be yelled at. They did not know all that was going on inside of me. But they bore the brunt of my full expression of pain, anguish, and frustration. Frankly, all of these feelings were rooted in my sense of vulnerability and impotence to guard those I love most from the fully marshalled and targeted power of white supremacy and the militarism of the state.

All my pain from not being able to protect those I love was poured out on those closest to me, whom I loved most. Yesterday was not my best day as a father. Yesterday was also not just about yesterday.

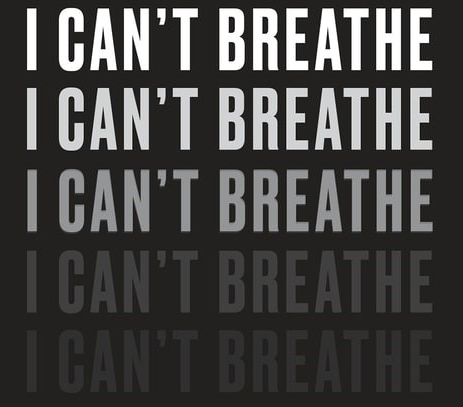

My words yesterday were about the pain of processing Black death from Memorial Day when officer Derek Chauvin choked the life out of George Floyd…and we watched. The heightened audible tone yesterday, was about visualizing young Ahmaud Arbery jogging through the neighborhood (the same way I do with my oldest son) being cut off and killed by a former police officer, teaching his son that black life is worthless. My intensity yesterday was about imagining my daughter standing, like Breonna Taylor, in the hallway of her own home being cut down by the bullets of a blundering police force who should have never been there, looking for someone they already had in custody.

And to be honest, I am absolutely sure that my emotions had still not come down from May 21st. On that day, I stood in the pulpit of First Baptist Church of Elmwood Park six feet from Pastor Brian Jackson, the mayor of Beverly Hill, Missouri to eulogize his aunt, Mother Viola Hill. At the age of 91 years, this elder of Saint John’s Church (The Beloved Community) where I pastored for ten years succumbed to COVID-19, which she contracted in a local nursing home. Not more than ten members of her inner circle of family and friends could pay their respects. But, how could they anyway?

How do you handle…process…make sense of Black Death?

In Mother Hill’s eulogy I reflected on the last time I spoke with her, May 4th. They had just placed her into hospice, and she was experiencing respiratory failure. She should not have been on the phone, but she had a few things to tell me. And, you always listened if she had something to say. So, she spoke, pushing out the words over short, shallow breaths. In the pulpit it reminded me of a dark-skinned, Palestinian Jew who died experiencing respiratory failure by way of asphyxiation in a public execution by the State.

Earlier yesterday afternoon, when I heard the autopsy report for George Floyd from Minneapolis, I was reminded once again. Death by asphyxiation at the hands of a representative of the State. Black death.

In the mid-1300s, a pandemic swept across the globe killing up to 200 million people. In a May 6th appearance on MSNBC, Anand Giridharadas, the author of Winners Take All: The Elite Charade of Changing the World, compared COVID-19 to the earlier wave of grief and loss with a rhetorical connection to America’s original sin. He said, “This is a crisis that in many communities is literally a ‘Black plague,’ that is killing African Americans disproportionately in part because people are not listened to in the healthcare system, in part because of lack of access.”

The novel coronavirus has comparatively only reached 6.2 million documented cases and 372,752 global deaths. But, in the last two weeks, it has spiraled into a massive, fatal public collision with what the Rev. Dr. Otis Moss III of Trinity United Church of Christ in Chicago, calls “COVID-1619,” the viral agent of racism and white supremacy which has infected American history for more than 400 years. This health crisis of anti-Black racism is deeply, structurally embedded in all aspects of American life and is enforced by the criminal legal system and its police.

Add to any of this the sense of nihilism, vulnerability and impotence which I experienced bouts of yesterday and Black Death can lead to depression, more death and destruction. You could end up yelling at the kids you love for things they don’t understand. You could end up harming yourself. You could take your sense of pain and weakness out on other people’s property under the veil of public protest…or worse.

I am sure that how I handle Black Death is not appropriate by anyone’s book. At least no one with credentials. Frankly, I’m not sure exactly what one could do to be credentialed in processing the Black Death within one’s own soul and spirit. So, I come to the community as I came to my sons. Confessing my shortcomings and asking for grace.

Inasmuch as I must confess and ask for grace, I am called to extend grace to all Black people who are wrestling with the reality of black suffering and death. I must extend grace to people without my privilege, my stability, my language and my access to be heard who process Black Death in ways for which they themselves may later confess, apologize and ask forgiveness. I commit to love them in their pain and folly as much as I love my boys.

Also published in The St. Louis American

Rev. Dr. Starsky Wilson is president & CEO of Deaconess Foundation and board chair for the National Committee for Responsive Philanthropy. He formerly co-chaired the Ferguson Commission. Follow him at @revdrstarsky and @deaconessfound.